14: Reading other people’s code will always be a bad user experience

First, my bold statement is this: reading other people’s code will always be a bad user experience.

The reason is simple: code readability is mostly subjective.

In year 2000, I had to set up Mailman for the company I was working and maintained the application for a few months. I remember when I first read its source code, I was so amazed how beautiful and elegant the code were. Today, I just tried reading some of them again, I was like, “that is not easy to read at all”.

This week’s idea is: I am making a list of standards when reading other people’s code.

(1) The reason of reading

I was exhausted when I tried to read the source code of Mailman again. More importantly, I no longer have any need to understand it and I also do not remember how to write Python.

The motivation of reading the source code is probably the first important element. If I don’t have to run it, test it, and even maintain it, it’s unlikely I will ever like it.

The take-way message is:

Do not judge other’s code when you don’t have enough context unless you are going to take responsibility with it.

(2) The stage of the project

I will give an example of this point. The example is written in Scala. Let’s say I have an entity like this:

case class Entity(field1: String, field2: Int)I would like to validate the fields, so I can start with this simple class:

class Validation1 extends Logger {

def validate(e: Entity): Option[Entity] = {

if (e.field1 == "hello") {

logger.info("I say hello")

None

}

else if (e.field2 == 10) {

logger.info("10 is a bad number")

None

}

else

Some(e)

}

}I hope it’s easy enough to understand. The problem of this version is: I have to do if-else statements and when I have more validation logic, this function will become very ugly.

Therefore, I can refactor it to the following version:

class Validation2 extends Logger {

def validate(e: Entity): Option[Entity] = {

for {

_ <- noHelloRule(e)

result <- noTenRule(e)

} yield result

}

private[this] def noHelloRule(e: Entity): Option[Entity] = {

if (e.field1 == "hello") {

logger.info("I don't say hello")

None

}

else

Some(e)

}

private[this] def noTenRule(e: Entity): Option[Entity] = {

if (e.field2 == 10) {

logger.info("10 is a bad number")

None

}

else

Some(e)

}

}

What I am doing now is: each rule becomes a function so I can use a for-comprehension to connect them together.

However, the problem of this version is: the class has 2 private functions and all of them have to be invoked inside the main validate function. If I need to add more validation logic, I will add one private method, and then update my main function. It’s annoying.

Hence, I can refactor one more time.

trait Rule[A, Result] {

def validate(e: A): Result

}

trait EntityRule extends Rule[Entity, Boolean]

case class NoHelloEntityRule() extends EntityRule with Logger {

override def validate(e: Entity): Boolean = {

if (e.field1 == "hello") {

logger.info("I don't say hello")

false

}

else

true

}

}

case class NoTenEntityRule() extends EntityRule with Logger {

override def validate(e: Entity): Boolean = {

if (e.field2 == 10) {

logger.info("10 is a bad number")

false

}

else

true

}

}

class Validation3 {

private[this] val rules: List[EntityRule] = List(NoHelloEntityRule(), NoTenEntityRule())

def validate(e: Entity): Option[Entity] = {

if (rules.forall(_.validate(e)))

Some(e)

else

None

}

}

In this version, each validation logic becomes a single class with a single purpose because it represents only one rule. The Validation3 class has a local variable holds all the rules. I am hard-coding the instance of the concrete rules, but later I can use different approach to inject rules dynamically. For example, I can use config file or attribute decorating a rule class, and then use reflection or meta to discover them.

Now, the question to ask is: why the heck I would do the third option at the beginning of the project, or with only a few validation rule and each of them is just a simple if-else?

Wait, some smart people might interrupt me. The third option is not Scala, or not pure functional at all. They are probably right. However, the take-away message is this:

It’s better to avoid over-engineering at the beginning. Instead, focusing on how to get the requirements right and readable, as well as validating the implementation with stakeholders, as opposed to overly generalize or optimize the implementation in the early stage.

(3) the context of the product and the company

As I mentioned earlier, code readability is highly subjective. However, my personal belief is: all programming languages are the same fundamentally. Proper choice of algorithm and data structure, separation of concerns, and SOLID (or following some similar principles) are more important than particular language syntax.

This should be particularly true when building commercial software. Writing pure scientific applications could be a different story. The reason is: after the product is launched, 6 months later, people might not remember what the code is about. Because of all kinds of staff turnover, for example, original dev team has been switched to a different department, or external team has finished contract, some new people will end up maintaining the code-base they have no idea of. Those poor guys could be as dumb as me, or they could be any level, but they need to be fast enough to debug and enhance the application.

Here is a bottom-line, especially for people do not believe it: business software needs to be maintainable and enhance-able by any software developer, as long as they know how to compile, code, and test. Therefore, the take-away message here is:

Depending on the type of the project and the company you are working for, simplicity is always the key. We are never writing code for ourselves. We are writing code for, one day, another person has to add a new feature to it or debug why it fails. Always KISS (Keep it simple and stupid), but flexible (so other people can easily change).

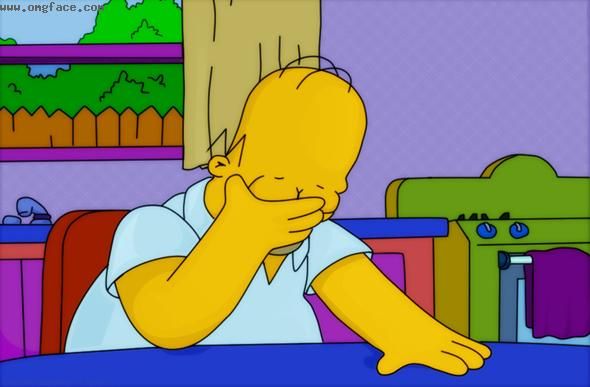

In conclusion, I believe we should refer to at least above 3 points before judging people’s code. However, as a software engineer, I know no matter what I say, people will always have this expression when they read other people’s code.